It’s Black History Month! We’re here to help you study up on your Black transit history. And while you’re here… How ‘bout a quick action to advance racial equity in transportation in our own day? Sign in PRO on House Bill 1301, to help us decriminalize fare non-payment. If this bill passes, Sound Transit can no longer tell us that state law forces them to rely on court-issued civil infractions when riders can’t pay. The deadline to complete this action is 2:30pm on Monday, Feb. 8.

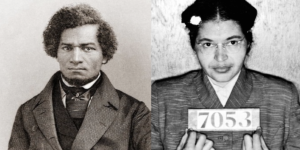

The real Rosa Parks & the long history of Transportation Protest

“Over the years, I have been rebelling against second-class citizenship. It didn’t begin when I was arrested.”

“Over the years, I have been rebelling against second-class citizenship. It didn’t begin when I was arrested.”

“I don’t believe in gradualism, or that whatever is to be done for the better should take forever to do.”

The story of Rosa Parks and the Mongomery Bus Boycott you learned in school wasn’t just skewed, it was way less interesting than the reality. The New York Times breaks it down.

Rosa Parks’s act of civil disobedience is only the most famous in a long, long history of Black people protesting segregated transportation systems. This history goes back at least to Frederick Douglass, who along with a friend in 1841 refused to leave a train car reserved for white passengers in Massachusetts. Their action led to organizing that resulted in Congress passing the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which granted Black citizens equal rights in public accommodations— until it was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1883. Read more about the history of civil rights transportation protests here.

Safe Bus: Transit Mutual Aid

In 1926, in segregated Winston-Salem, NC, 13 Black jitney operators banded together and founded Safe Bus, a bus company to serve the Black neighborhoods where the privately-operated streetcars didn’t run. It grew to 75 employees and at one point was called the largest Black-owned transportation company in the world. In 1966, 20-year-old Priscilla Estelle Stephens became the first female driver for Safe Bus. Eventually, in 1972, the company was bought by the city and integrated into the public transit system.

In 1926, in segregated Winston-Salem, NC, 13 Black jitney operators banded together and founded Safe Bus, a bus company to serve the Black neighborhoods where the privately-operated streetcars didn’t run. It grew to 75 employees and at one point was called the largest Black-owned transportation company in the world. In 1966, 20-year-old Priscilla Estelle Stephens became the first female driver for Safe Bus. Eventually, in 1972, the company was bought by the city and integrated into the public transit system.

The Real McCoy: Black ingenuity advancing transportation

Black inventors have left their mark on transportation history. Back in the 19th century, inventor & engineer Elijah McCoy, a child of escaped slaves, developed new lubricants for railroad steam engines. It may be apocryphal, but they say the superiority of his products led railroad engineers to ask for “The Real McCoy.”

Black inventors have left their mark on transportation history. Back in the 19th century, inventor & engineer Elijah McCoy, a child of escaped slaves, developed new lubricants for railroad steam engines. It may be apocryphal, but they say the superiority of his products led railroad engineers to ask for “The Real McCoy.”

Andrew Jackson Beard, a former slave who became a flour-mill owner and then an inventor, created a device that automatically joined railroad cars together, eliminating the need for a worker to stand between two cars to drop in a metal pin— a dangerous job that sometimes led to the worker being crushed.

Granville T. Woods, the first African American mechanical and electrical engineer after the Civil War and a prolific inventor, authored many transportation-related inventions— notably the Synchronous Multiplex Railway Telegraph, a device that allowed for communication between trains.

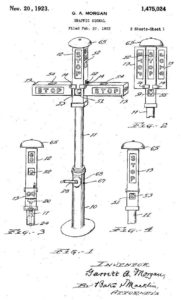

Garrett Augustus Morgan, a child of freed slaves, was a businessman, inventor and community leader. After witnessing a serious vehicle crash, he invented and patented one of the first three-signal traffic light systems in 1923.

Philadelphia Transportation Company strike: It ain’t all pretty

Labor unions have a complicated track record when it comes to race. Some unions have been staunchly anti-racist, all about forging multiracial solidarity. But at other times, white workers have banded together not just to fight the bosses, but to protect their privilege and their jobs from competition with Black workers. That happened, big-time, in Philadelphia during WWII.

Labor unions have a complicated track record when it comes to race. Some unions have been staunchly anti-racist, all about forging multiracial solidarity. But at other times, white workers have banded together not just to fight the bosses, but to protect their privilege and their jobs from competition with Black workers. That happened, big-time, in Philadelphia during WWII.

The Philadelphia Transportation Company, which operated the city’s trolleys, buses and subways, employed Black workers as porters and tracklayers but refused to hire or promote them as drivers or conductors. Effective organizing by Black-led civic groups and churches led to the federal Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) ordering the company to promote Black workers.

But the white members of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Employees Union were not pleased. They walked out and shut down the entire Philadelphia mass transit system for five days. The conflict spread to the streets where Black protesters retaliated against white-owned businesses, smashing windows and slashing police tires. The strike was ultimately broken by federal troops sent in by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Within a year, large numbers of Black workers had been promoted.